In Lunenburg, on the South Shore of Nova Scotia, a technocolour history of the Maritimes reflects off the water, more than 200 years of heritage sitting at sea level, the paint on the buildings worn yet still somehow preserved and pristine. Deemed a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the old town colonial settlement has withstood over two centuries worth of hurricanes and tropical storms. But when Hurricane Dorian made landfall northeast of Lunenburg on September 7, 2019, tearing roofs off houses and crippling power lines, something felt different.

In the aftermath of the costliest hurricane to ever hit Nova Scotia, new, startling possibilities emerged. The town had never been hit so hard by a hurricane and storm surges within both the front and back harbours caused extensive flooding and damage. Water flooded the Wastewater Treatment Plant and in an interview with the local news, Lunenburg’s then-Mayor Rachel Bailey said, “There was seawater from our back harbour that was in places it had never been before.”

With the plant unoperational, the town was forced to dump unfiltered sewage into its harbour. It was a pivot point, one of those “never again” moments that divides neatly between before and after, a new reality that prompted the town to take action to prepare for rising sea levels and the threat they pose to coastal communities like Lunenburg. But in order to do so, the town needed a new language for understanding the effects of climate change.

3D technology born from the storms of Nova Scotia

Some ideas flicker into life like a lightbulb, like they’re plucked from the ether. But the idea for 3D Wave Design, an innovative, Indigenous-owned modelling and mapping service, was born of Dorian and the storms over the past decade and a half lashing the Maritimes. For Barry Stevens, a Mi’kmaw from nearby Mahone Bay, Hurricane Dorian sparked the realization that mapping storms isn’t the problem. The bigger problem is getting coastal communities ready for rising sea levels due to climate change and how it intensifies storms.

“Lunenburg’s coastal location and its economic and social reliance on the waterfront make it particularly vulnerable to climate change effects like sea-level rise and increased storm surge.”

Today, Coastal Action, an environmental non‐profit organization, is leveraging support and funding from partners including RBC Tech for Nature to pilot 3D Wave Design’s cutting-edge mapping technology and living shorelines that utilize vegetation and natural materials to help prepare citizens, governments and business owners in Lunenburg and nearby Mahone Bay for the effects of rising oceans and climate change.

“Most people live as if things are always going to be the same,” says Stevens, who co-founded 3D Wave Design with his son, Noah, a 3D artist and developer. But in Nova Scotia, on the coast, it’s there — change isn’t just a feeling, it’s visible in the water levels, that inconvenient, brackish line.

You go to Historic Properties in Halifax and when it's high tide it's inches from ingressing on top of the old wharves. How can you deny that? I think people get overwhelmed and they think it's someone else's problem but it's not someone else's problem. It's our problem. And it's our kids' problem. So it's time to move on this stuff.

Barry Stevens

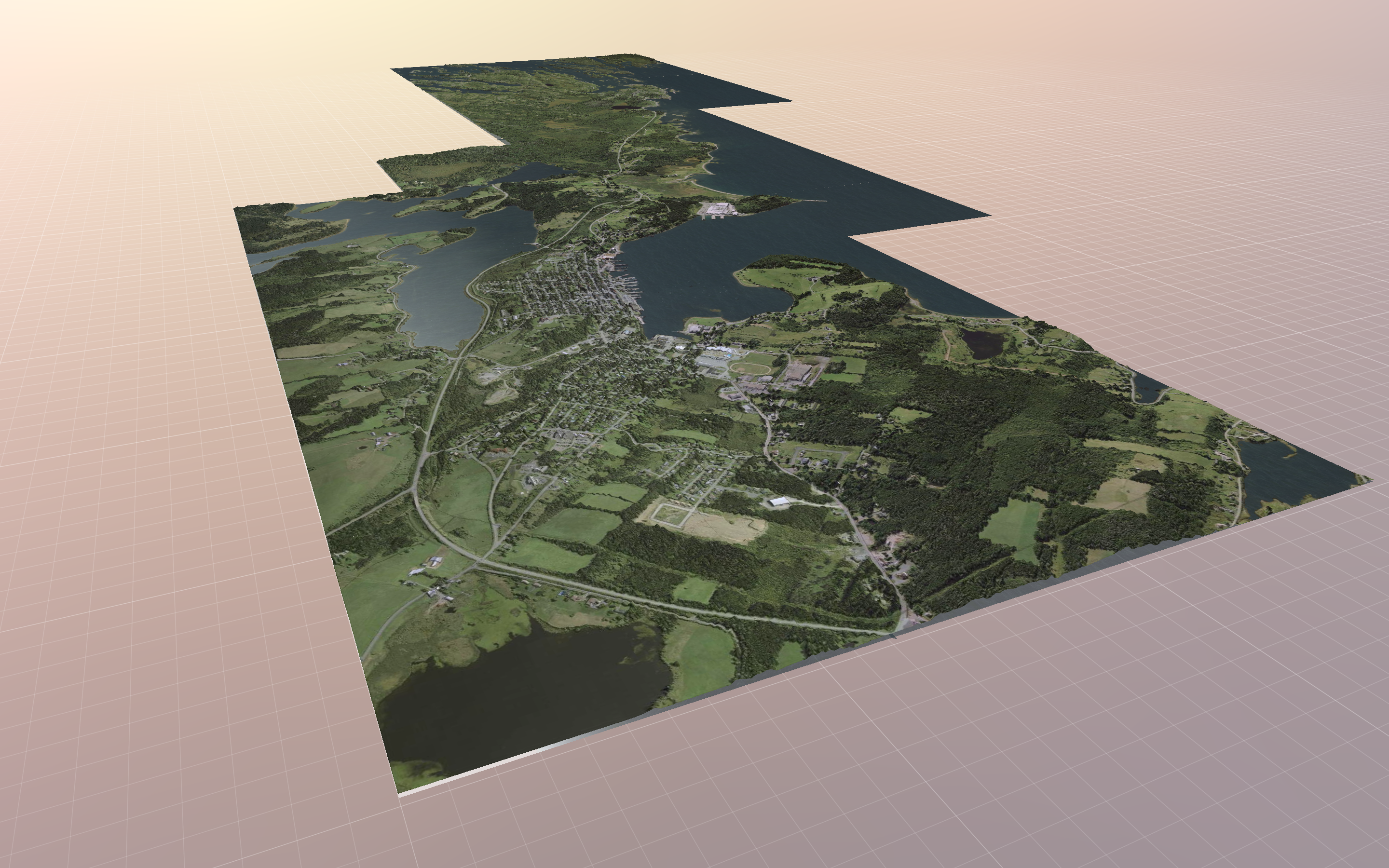

A 3-D aerial rendering of Lunenburg and the surrounding area.

A 3-D aerial rendering of Lunenburg and the surrounding area.

A new way to visualize rising sea levels

It should be simpler to talk about sea-level rise but it’s not. The current mapping system, which uses high-definition imagery from LiDAR (a laser-powered sibling to radar) and supercomputers to create topographical maps doesn’t always do a good job of illustrating the notion of sea rise to the average person. 3D Wave Design aims to solve that disconnect by converting huge LiDAR data files into 3D models small enough in file size to be manipulated in real-time in a web browser. Users can easily adjust tide height and projected storm surge settings.

The simplicity of the concept is what helped catch the attention of Coastal Action, an environmental organization that focuses on research, education, and action surrounding watersheds and water quality, species at risk and biodiversity, climate change, environmental education, and coastal and marine issues.

Samantha Battaglia, Climate Change team lead at Coastal Action, says she and Stevens connected at a workshop on sea-level rise and discussed the potential of a visual mapping tool to help engage and communicate coastal climate change risks and impacts to the general public and municipalities.

Check out 3D Wave Design’s Mapping Tool developed for Coastal Action.

“I think a lot of the models or maps that are already out there that give people an idea of which areas and infrastructure might be at risk to flooding aren’t detailed enough,” explains Battaglia. “It’s hard for the user of the tool to visualize themselves or their home because they often don’t include visual landmarks that give you enough detail to identify specific areas in your own community that might be at risk.”

Climate change can also be a challenging and politicized conversation.

The topic of sea-level rise and storm surges and how it's going to affect people's homes can be very alarming. If it's presented in certain ways, it can be seen as fear-mongering, so finding a way to tactfully engage communities, identify risks, and illustrate impacts is a challenge.

Samantha Battaglia

With the Lunenberg pilot, Coastal Action has embedded resources in the 3D flood modelling platform like tide and weather data, historical photos, and information about nature-based solutions that can be used to help protect or buffer the impacts of storm surge and flooding for coastal infrastructure and land. Together, Coastal Action and 3D Wave Design are creating a new language for talking about climate change and rising seas.

Both Battaglia and Stevens see it as a way for emergency planners to plot out muster stations and safe emergency evacuation routes. Its ease of interpretation makes it ideal for quickly identifying at-risk coastal areas and infrastructure in real-time during storm events. But it’s more than that, says Battaglia. “For planners, residents, developers and municipalities, this tool can be used to identify low-risk areas for siting, purchasing, or building future infrastructure and it can be used to identify high-risk areas where adaptation is needed.”

Since its inception in 2019, RBC Tech for Nature has brought together more than 125 organizations to protect the world’s most precious resource – our natural ecosystem – through tech-based community investments

RBC Tech for Nature is a core pillar of RBC’s Climate Blueprint — an enterprise strategy to accelerate clean economic growth and support our clients in a socially inclusive transition to net-zero.

Protecting coastal homes and businesses as water levels rise

Brian MacKay-Lyons is sitting in his office at B2 Lofts looking out at the harbour in Lunenburg. The architect and co-founder of MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects is always thinking about sea-level rise.

“We probably should’ve thought about it more before we built our office that I’m sitting in right now,” he says. “It’s really in the lowest part of the town where it comes closest to sea level.”

MacKay-Lyons is renowned for designs that reflect the heart of coastal Nova Scotia — many of which stare down the ever-rising Atlantic.

“Certainly it’s an issue you have to think about now and everybody’s aware that it should be considered.” — Brian MacKay-Lyons, founder MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects

A lot of projects he works on use LiDAR information and simulations to model changes to sea levels. “But we don’t have the ability to really know.”

MacKay-Lyons likens architects to conductors in orchestras. “The architect has the most influence on what the concept is of a project at the outset because the architect is the one who’s looking at all the systems … you have to know a little bit about all the instruments in the orchestra.”

He says a tool like 3D Wave Design could ultimately make it easier to communicate with the different players in the orchestra of design he conducts. It’s about accessibility to information.

In a lot of ways, that’s the elegance of 3D Wave Design’s mapping tool — it creates more informed coastal citizens. It has the ability to affect change. Especially in Lunenburg where it’s being piloted. Lunenburg makes sense. The town is both a metaphor for coastal communities across the world and a place where you can stand and watch the effects of climate change lap at your feet.

The amount of time between storms of a given magnitude is decreasing. In the next 30 years or so, our ‘100-year storms’ will be our ’25-year storms.’— Nova Scotia Environment’s Climate Change Unit

Stevens talks about moving the slider in the 3D Wave Design interactive tool and watching the sea level rise. He points out that the wastewater plant lies in low-level land, a connection between the open harbour and the back harbour that served as a Mi’kmaq portage route for centuries. “It was a real eye-opener, their new fire department is at risk, their new school is at risk, the old community center, the curling rink and hockey rink is inundated… anywhere where the Red Cross might pitch tents or park vehicles, it’s all underwater.”

It’s not just theoretical. While addressing the flood of the Lunenburg Wastewater Treatment Plant from Hurricane Dorian in 2019, the town has incorporated the 3D flood model. “Traditionally, an engineering study would have been focused on the single problem and the resulting recommendations would have been focused solely on solutions for that using present-day data,” explains Ian Tillard, consulting town engineer. “By including Lunenburg in the 3D model, it has provided us with a planning tool to assess the level of threat of sea-level rise and storm surge effects for the entire town.”

Tillard says the next steps are to incorporate the use of 3D Wave Design’s tool in the assessment of the effects of sea-level rise in future development, existing infrastructure and public safety. “That process is in the very early stages but ultimately, the 3D model will be used as a planning tool and incorporated as an additional step in the development process and asset management program.”

A photograph of the Nova Scotia coast near Lunenburg at sunrise.

Informing the future of Canada’s coasts

In Mahone Bay, 3D Wave Design’s tool is being used by Coastal Action to illustrate the effects of a living shoreline — a combination of rocks, tidal wetland and a raised bank covered in vegetation – that will help dissipate wave energy and reduce shoreline erosion. “We will be piloting a living shoreline project throughout the next two years in the Mahone Bay Harbour to help protect a 60 m stretch of Mahone Bay’s shoreline from flooding and erosion. This project includes the installation of rock sills, a tidal wetland, and a vegetated bank. These three components will work collaboratively to reduce wave energy and storm surge, filter stormwater runoff, and stabilize the shoreline.,” says Battaglia. It’s slated to begin in 2022 but with 3D Wave Design, it’s possible to model the effects.

“We’re creating a 3D model with the true hydrodynamic real-world physics of waves coming up onto the shore with and without the living shoreline,” says Stevens. It’ll help communicate how the shoreline attenuates the waves. 3D Wave Design is also looking at ways to use the technology to help First Nations communities.

“A lot of First Nation communities were forced onto land — lots of floodplains, lots of rocks, a lot of swamps,” says Stevens. “A lot of my fellow Mi’kmaq are at the highest risk because the good land was taken.”

He points to Lennox Island on nearby Prince Edward Island, a low island in constant threat of sea-level rise. “If I can get this in the hands of people they can figure out: If we’re going to continue living here, we’ve got to put a living shoreline in, this is the only way forward or we’ve got to move,” says Stevens. “We’ve got some hard decisions to make as a people, as Canadians and globally.”

RBC Tech for Nature is RBC’s multi-year commitment to preserving the world’s greatest wealth: our natural ecosystem. We work with partners to leverage technology and innovation capabilities to solve pressing environmental challenges. RBC Tech for Nature brings to life the fifth pillar of the RBC Climate Blueprint, our enterprise approach to accelerating clean economic growth.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.