The sharp whistle of a train engine greets you at the entrance of Impressionism in the Age of Industry: Monet, Pissarro and more, currently on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario. As though being ushered through a gate at Gare St. Lazare, Paris’ 19th century central station, you’re transported back in time to a place where steam, steel and speed were dramatically changing how people experienced the world. “It is an opportunity to reflect on the historical drivers of social change, and also to consider art’s role in offering us moments for reflection and contemplation, on how what is depicted might also resonate with our contemporary moment,” says Corrie Jackson, RBC’s Senior Curator.

Impressionism in the Age of Industry begins in 1850, as city planner Georges-Eugène Haussmann is completely redesigning, demolishing and modernizing Paris. This is the place where photography has just been invented, where people can now communicate quickly over great distances using the telegraph and gas streetlights allows city dwellers to stay out past sundown.

This is also the home of the Impressionists, a group of artists who were first renowned for the ways they painted fleeting moments in nature using daubs and dots of colour on canvas. The Impressionists were also driven to document the changes in their urban environment. This exhibition tracks how they interpreted, reacted to, and were inspired by the rapidly changing pace of life. The exhibit takes visitors through the hardships of the Franco-Prussian War to the celebrations of the 1900 World’s Fair, away from the city into the leisurely, pastoral suburbs and back downtown to the throws of bustling nightlife at dawn of the new century. In the brushstrokes of painters like Monet, Pissarro, Cassatt, Seurat and Degas, the precise detail of photographs by Marville and Collard, and intimate etchings by Bracquemond and Tissot, we witness the transformations of the industrial era through the artists who experienced it first-hand.

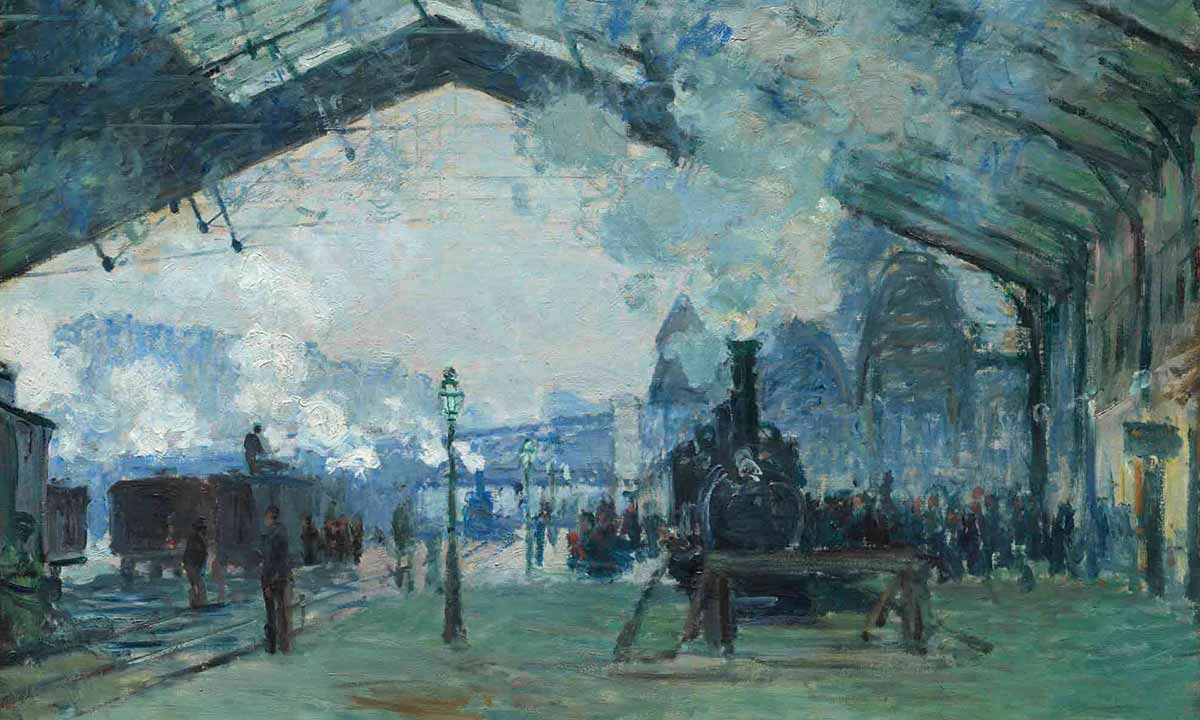

Claude Monet. Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint Lazare (detail), 1877. Oil on canvas, Overall: 60.3 × 80.2 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1158. Image © Art Institute of Chicago/ Art Resource, NY

While Monet’s name might bring to mind the serene shades of his Water Lilies series, here he uses smokey grey, cobalt and turquoise to depict the newly finished Gare Saint-Lazare, as well as labourers loading coal into boats on the banks of the Clinchy River.

Camille Pissarro. Le pont Boieldieu à Rouen, temps mouillé, 1896. Oil on canvas, Unframed: 73.6 × 91.4 cm. Gift of Reuben Wells Leonard Estate, 1937 © Art Gallery of Ontario 2415

Pissarro shows billowy factory smokestacks near Pontoise, bustling bridges near Rouen, and the newly completed Avenue d’Opera.

In the more than 120 artworks included in the exhibition are the Eiffel Tower, the Métro system and the Vendôme Column each at various stages of construction. Visitors are able to cross Gustave Caillebotte’s Pont de L’Europe thanks to a virtual reality simulation, and can wind their way through the city with the help of period maps, guidebooks and archival materials. One can almost hear the crash of metal and hammer happening in the kaleidoscopic, fiery depictions of steelworkers and pile-drivers by Luce, or the soft sway of wet fabrics in the paintings of laundry washers by Degas.

Edgar Degas. Woman Ironing, c. 1876-1887. Oil on canvas, Overall: 81.3 × 66 cm; Framed: 99 × 82.5 cm . National Gallery of Art, Washington Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon 1972.74.1.

Viewers are able to take a break on the banks of the Seine through Seurat’s intimate studies for Bathers at Asnières, and find themselves traipsing through newly ordered fields with Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Sérusie and Émile Bernard’s farmers and sowers.

Vincent van Gogh, Factories at Clichy, summer 1887. Oil on canvas, 53.7 x 72.7 cm. Saint Louis Art Museum, Funds given by Mrs. Mark C. Steinberg by exchange 579:1958. Image courtesy Saint Louis Art Museum

Throughout the exhibition, scenes of construction depicting cranes, scaffolding, glass, rivets and concrete are paired with those showing the people — laborers, factory owners, and shoppers— who were both instrumental in, and directly affected by industrialization, automation and commercialization.

Presented this way, visitors can see similarities inside and outside of the gallery. The exhibit’s dotted, almost pixelated paintings, the strikingly sharp photos and the silvery, cinematic compositions versus what you see in Toronto when you walk out of the exhibit where skylines rise higher and higher, information flows faster and faster, and high-speed travel shrinks the distances.

“Supporting the visual arts is essential to cultivating a dynamic and innovative culture in Canada”, says Jackson. “Being the lead sponsor of exhibitions like this one allows us to foster conversations that are sparked by reflecting on great work through new perspectives.” Impressionism in the Age of Industry visualizes the velocity of life in late 19th century Paris — a new city of steam, steel and speed. Here, the time and space of the Impressionist’s world is brought closer to ours and we may find in it more parallels to the pace of present-day than expected.

Find out more about how RBC supports the Arts.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.